Lower back pain is a real BIG DEAL for a lot of people and with all the opinion and dogma that gets attached to various exercise types surrounding it I thought I would take a little look at the EVIDENCE base to try and get some clarity on what really is the BEST exercise for low back pain (LBP).

We are in luck here too. The good folks of academia have blessed us with a plethora of studies to choose from, not just looking at if a certain type of exercise is effective for LBP but also comparison studies to find out if they are MORE effective than something else!

The evidence

Lets start off looking at one of the most popular methods touted to resolve chronic back pain…..Pilates. This study *HERE* looked at Pilates in comparison to a stationary bike program over 8 weeks. The results indicated that at a 6 month follow up, an important time measure for CHRONIC pain, there was no between group differences, both were effective for reducing pain, disability and catastrophising.

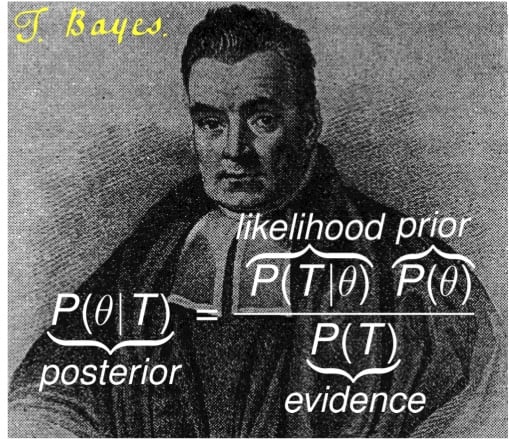

Interestingly at 8 weeks the Pilates group was performing significantly better than the stationary bike group but NOT at the six month follow up. Could this be due to receiving an exercise method PERCEIVED to be the most clinically relevant treatment and influencing the short term measure?

This result was also replicated with a larger look at the data in a meta analysis of core stability exercises versus general exercises for chronic back pain *HERE*. The authors concluding that core stability training out performed general exercise in the short term but not in the longer term.

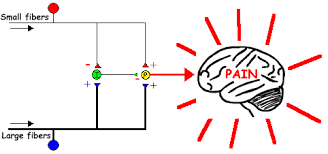

This paper found that a successful outcome for lower back pain using core based exercises was not associated with improved abdominal muscle function *HERE*. A positive effect of stability exercises has been postulated to be due to central mechanisms unrelated to abdominal muscle function. One reason could be the expectation being met of receiving the most PERCEIVED relevant treatment hence the shorter term success in the outcome measures. An expectation being met may activate mechanism’s such as the reward analgesia system.

Another systematic review with meta analysis provides the ‘coup de grace’ *HERE* concluding unequivocally:

"There is strong evidence stabilisation exercises are not more effective than any other form of active exercise in the long term. The low levels of heterogeneity and large number of high methodological quality of available studies, at long term follow-up, strengthen our current findings, and further research is unlikely to considerably alter this conclusion”

Next up we have a walking program compared to specific back strengthening exercises *HERE*. Both were performed twice a week for six weeks and a number of measures were taken. Again both groups improved but without much difference between them. It is important to note here that the participants were all sedentary to begin with so a take away maybe that the ACTIVITY here was the most important factor for those who do not do very much of it rather than the SPECIFICS of the activity.

Conventional wisdom may have us believe that a specific intervention, due to its targeted nature, should out perform the more general one and not just a bit but significantly. That does not seem to be the case however. Much more general exercise WITHOUT the need for specific instructions or exercise experience and expertise seems to be just as effective.

A classic ‘moan’ from the sycophantic supporters of failed treatments is “they did not do it right” shifting the blame over to the person. The good thing with a more general program is that we can say with a degree of certainty they are just as effective but without so much that can be done in the ‘wrong’ way.

This randomised control trial *HERE* looked at a higher loading exercise program versus a lower loading ‘motor control’ program for patients with ‘mechanical’ lower back pain. Here the lower load group outperformed the high load group in some measures but at the 12 & 24 month follow up *HERE* there was no significant difference in the outcome measures. So again we see no real differences between two quite distinct exercise programs with both making improvements.

There are some caveats here. Both groups received education about pain mechanisms and, gulp, non alignment and optimal movement (whatever that is). As both groups shared this, it could have been an influence on the outcome. The low load group also did a greater variety of movements rather than just the deadlift performed by the higher load group. There is data, that we will get to later, that suggests reduced variability could be a factor in cLBP hence a healthy dollop of variation of movements performed could have had a positive effect.

A comprehensive paper “Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials” found beneficial effects for exercise over thirty nine RCTs with a small but SIGNIFICANT effects on lower back pain for both strength/resistance AND coordination/stabalisation programs. The largest effect size was seen with exercise programs that focused on the WHOLE body which tended to be strength/resistance based. The important take home here is that exercise interventions were deemed more beneficial than other treatments.

The EVIDENCE of ANY real superiority of one type of exercise over another seems to be lacking here. Anyone who tells you they have a SUPERIOR ‘method’ maybe over egging the pudding!

What does that mean? Well exercise that gets DONE will probably be the most effective. Some questions worth considering are:

- What activities do people ENJOY?

- How easy is it for them to do?

- How relevant is it to their functional outcome measures?

- Are they easily able to access the necessary equipment or need specialist instruction?

I discuss the effect of environment and access *HERE*.

A focus on the HUMAN BEING doing the exercise rather than just their back might be just the ticket!

A good rehab program should be well rounded and encompass lots of factors associated with human function rather than trying to find the magic bullet of one type of exercise. Imagine if athletes only ever practiced one type of exercise! A combined approach to physical rehab could be beneficial incorporating variation in movements, high and low loads and specific and more general components.

An approach to lower back pain that considers lots of different aspects around movement is by Nijs et al *HERE*. It fits all my biases of people’s individual relationships with movement/exercise therapy for their back pain and the multiple factors to be considered across both the cognitive and physical realms.

It is also important to think about other factors associated with LBP and not just get hung up on exercise *HERE* and *HERE*

Deconditioning

So it makes sense that if exercise works for lower back pain then it maybe due to the fact that people need to get a bit stronger or some more endurance and that performing exercise helps with this.

Like lots of things that seem to make sense in regards to the body it is not so clear cut when we delve in a bit deeper. This systematic review *HERE* concluded that the positive effects from exercise for LBP were NOT directly attributable to things such as strength, mobility or endurance.

Deconditioning has often been linked to lower back pain and hence the idea of reconditioning as a cure for lower back pain. This did not seem to be the case in this study *HERE* that looked at physical deconditioning in the first year following the onset of back pain.

Perhaps this adds to the argument that the DOING of exercise in more important than the type or the targeted physical aspects e.g. strength. The potential for the PSYCHOLOGICAL effects to be as important, or even more so, than the physical seems highly plausible and is certainly food for thought.

Being physically active is often touted as both prevention AND cure for LBP. This paper *HERE* suggests that it is not that clear cut, surprise surprise, looking at it as being more of a U shaped relationship. They found a moderate increase in cLBP risk with both a sedentary lifestyle OR excessive activities so more does not simply equal better when it comes to exercise.

This systematic review with meta analysis *HERE* DID find, although no discussion of the bottom and top ends, low to very low evidence that exercise alone reduces incidences of LBP and moderate evidence that combing education with exercise also helps.

As usual the deeper we delve the less clear it becomes and why we should be wary of simplistic answers and cures that are usually based around doing the one BEST thing such as activating a muscle or correcting a pelvic tilt.

Are there any physical ‘deficits’ or characteristics we see with LBP?

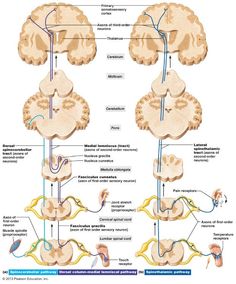

Laird et al looked at lumbo pelvic MOVEMENT in people with AND without back pain *HERE*. Their systematic review found, in comparison to those NOT in pain, reduced proprioception (15 studies), slower movement (8 studies) and reduced range of movement in all directions (26 studies)

Nourbakhsh and Arab *HERE* DID find that muscle endurance and weakness WERE associated in their sample size of 600. This however does not imply that these factors were a cause of LBP especially with the type of the study performed.

Both papers also looked at some structural factors and their association with LBP. NEITHER paper could find an association between lumbar lordosis angle or pelvic tilt angle. Nourbakhsh and Arab also investigated the association of leg length discrepancy and abdominal, hamstring and hip flexor length with LBP and found none.

This paper *HERE* looked at the spine loading characteristics of those with and without back pain. They found INCREASED spine loading for those with LBP and significant increases in all of the 10 muscles studied using EMG data. They also found the LBP group had severely restricted motion in a free lifting task. They concluded that the increase in spinal loading was due to INCREASED muscular co-activation.

Trunk stiffness in this study *HERE* was related to fear of movement in those suffering from LBP. Greater kinesaphobia fear of movement) resulted in greater trunk stiffness.

So we have kinematic and muscular data suggesting that those suffering from LBP have GREATER muscle activation and co activation and REDUCED movement around the lumbopelvic area. This makes sense if we see muscular responses to pain as being PROTECTIVE in nature and aiming to minimise movement in this area due to pain or the perceived THREAT of pain.

Here is a bit of opinion based on the data.

How do exercise strategies that promote core stiffness such as many popular approaches for LBP affect this? Could they perpetuate the problem rather than solve it? High loading strategies may also promote increased stiffness, could this have the same negative effect?

Could a key be being able to ‘turn off’ muscles as much as we are trying to ‘turn them on’? Potentially choosing the right amount of muscular activation and stiffness for the task is the sign of ‘healthy’ movement rather than just increased ‘activating’, ‘firing’ or whatever you choose to call it. Reduced movement may not be under activation of a muscle but increased activation of another to stiffen the joint.

Freedom of movement, both physically and psychologically, should be an aim for those working with people suffering from lower back pain.

Variability

As it’s my blog I get to indulge in some my biases! One of those is movement variability. There is a reasonable amount of data in my opinion that suggests decreased movement variability is associated with LBP.

This first paper supports some of the kinematic changes we see around the trunk discussed in the section above. The authors *HERE* looked at the coordination patterns between the trunk and the pelvis during running and walking comparing different groups. As loads increased during running, variability in pelvis and thorax rotation decreased on a continuum between the no LBP group, one bout of LBP and then the chronic LBP group. The decrease in variability could be due to the increased trunk STIFFNESS noted in other papers.

Lamoth et al *HERE* found a more rigid, less flexible pelvis-thorax coordination variability (counter rotation) as walking velocity, and therefore demand, increased. This decrease in thorax to pelvis motion was also present in a study by Van Den Hoorn *HERE* and also attributed to increases in trunk stiffness.

Falla et al found reduced ranges of motion in a free lifting task with the LBP group in their study *HERE*

As well as looking at the kinematics they also explored INTRA (within) muscular activity using EMG. They found significant higher values for EMG activity for the LBP group, consistent with other studies, to accompany the reduced kinematics of the spine indicating a stiffer strategy.

The LBP group also displayed decreased variability in muscular strategy, not displaying the shift in activity to different muscular regions that the pain free group did. This repetitive muscular strategy was accompanied by an increase in LBP, reduced lumbar movement and increased pressure pain sensitivity.

Decreases in variability have also been linked to chronicity in back pain *HERE*

What does this variability stuff all mean?

Well it could be that simply decreasing trunk stiffness may automatically increase variability. It may also be that focusing on decreasing stiffness through more relaxed movement across a variety of tasks, such as gait, could be a treatment strategy for LBP sufferers.

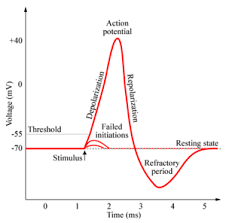

Could this increase in stiffness and decrease in variation also play into intra muscular metabolism? This could potentially increase ongoing sensitivity via mechanisms such as changes in local tissue PH and excitation of acid sensing ion channels in afferent neurons.

Whilst looking at variability is a promising avenue, and worthy of exploration in my opinion, I do discuss some of the limitations currently present here in this line of research *HERE*

Conclusion

- Lots of different types of exercise have a positive effect on LBP.

- No one type seems to be superior.

- Focus on the HUMAN BEING not just the back.

- Exercise that people enjoy and is easy for them to do will probably get done and hence have a positive effect.

- Consider a rehab program combining different exercise variables e.g. high and low load and types rather than one singular type or exercise method.

- Deconditioning is not clearly associated with LBP.

- Positive effects from exercise for LBP may NOT be directly attributable to things such as strength, mobility or endurance.

- Increased trunk stiffness and decreased ROM and speed of lumbar movement ARE associated with LBP.

- Structural factors such as lumbar lordosis, pelvic tilt, leg length discrepancy and muscle length are NOT likely to be associated with LBP.

- Kinematic AND intramuscular reduction in variability is associated with LBP.

- Decreasing stiffness and promoting freedom and variability of movement maybe a good goal in rehab, especially with those displaying kinesiophobia.