Exercise dosing for pain is NOT the same as exercise dosing for fitness!

Exercise dosage in rehab is still one of the biggest areas of uncertainty in clinical practice. On one hand we have modern thinking that promotes higher loading & dosage for patients and on the other hand we have the traditional model of lower load and lower dosage that has probably evolved to minimise the risk of adverse scenarios such as increased pain and decreased patient confidence in the therapist.

Currently we have some basic dosage guidelines for rehab that focus on the physical qualities that we know can be a PART of rehab. But if we take the primary target of the majority of rehab, PAIN, and if we are being honest with our current knowledge base, we don’t really have the sets and reps, or other dosage parameters that we can use to achieve a reliable outcome on our patients pain.

If we look at the current research base for rehab exercise we regularly see that the confidence intervals around the mean effect for pain cross zero meaning that the possibility of a large, small, no or even an adverse effect are all still a possibility.

Rough current physical dosage parameters

- Endurance 12+. 2-3 sets.

- Hypertrophy 6-12, 3-6 sets.

- Strength 6 or less, 2-6 sets

- Power 1-2 reps, 3-5 sets.

Unfortunately NONE of these things relate well to pain and that makes a lot of sense but also throws in some confounding. We know pain is a multi dimensional experience so for one factor to reliably relate well to pain makes little sense, but the issue is that the one factor (exercise) may also have an effect on multiple dimensions associated with pain as well, so this becomes a little confusing : ). Maybe the key here is the word reliable?

So if we want to improve these physical

aspects in rehab then we do have some parameters to work with. The question is

can we simply port over what we know about exercise over to rehab exercise and

pain?

I don’t personally believe so.

So Lets NOT say physical parameters are unimportant but also acknowledge that expecting a traditional view of exercise and exercise dosing to have a predictable effect on pain may not be prudent or correct.

A principle often discussed in relation to exercise programing is the SAID principle, Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demand, this means that the body will always adapt to the stimulus applied. Now this is a principle that will hold true always, although HOW the body adapts is still pretty individual and often not easy to predict.

BUT the problem is that we expect the thing we can specifically target with our current dosing knowledge, lets say strength with a rep range of 6 or under and a load that reflects that, will have a predictable and specific relationship with ANOTHER therapeutic target, PAIN.

So we are not really being specific in this case at all as there is a disconnect between the targeted physical outcome, and associated dosing parameters, and the outcome of pain.

Rather than just physical adaptations, a modern view of rehab might start to think about some of the things that exercise might affect that have a positive impact on patients. To get a specific effect from these things we might have to think about programming specifically to achieve these outcomes rather than suggest our current rehab dosing will automatically improve them.

Therapeutic exercise targets:

- Pain (the big confounder)

- Specific functions (physical qualities are a part of but not all of this)

- Fear avoidance & psychological measures (proving very important in outcomes & prognosis)

- Confidence & motivation

- Freedom of movement/relaxation

- Movement strategy

- Adherence

Exercise Research

If we take recent work by O’Neill HERE that looked at acute analgesia (instant pain relief) we see that the set dosage used in this study, looking at individual responses, produced variable responses on pain, even INCREASING pain, especially if the patients baseline pain was already high. 5

Another paper HERE looks at different exercise types effect on pain and an interesting recent paper HERE discussing mechanisms and individuality with pain responses to exercise.

Lets take a look at some exercise comparison studies where pain was part of the primary outcome measure. We see that different programs with different dosing parameters have similar outcomes. We also have to be aware that if we are looking at the mean effect of exercise on pain this may mask the low and high responders to the differing dosage levels.

This study HERE compared low and high load exercise programs for rotator cuff tendinopathy

This study HERE compared high (deadlifts) and low load (motor control exercises) for back pain. The conclusion from this group’s research was that higher load was more applicable for those with lower pain.

This study HERE looked at different loading programs for Achilles tendinopathy

Tolerance

Exercise for pain perhaps should not

always be seen as something that will reduce pain in the short term, as we

might see with the concept of exercising/moving to change symptoms. Instead it

might be moving with a TOLERABLE amount of pain that increases pain self

efficacy and keeps the body moving during pain is an equally important

scenario.

Remember tolerance should really be

PATIENT DEFINED. Exercise has the potential to increases our patients pain as

well as reduce it and anyone in clinical practice who has flared a patient up

with exercise knows this! The concept of optimal loading is really about tissue/physiological

adaptations, but perhaps we also need to apply this optimal loading concept to

pain adaptations, increases in pain, staying within current symptomatic levels

and also decreases in pain.

We know that exercising WITH pain does not produce worse outcomes HERE. I have previously written about this HERE

Current state of the patient

So within the concept of tolerance we have to consider the current state of our patient with regards to dosage. It is tough to reconcile the concept of tolerance within a model of changing strength, ROM etc for me, as this does not consider things that might affect our patient’s tolerance to exercise.

Things that might affect our patients pain tolerance

- Current/previous levels of exercising

- Stress levels

- Sleep behaviour

- Anything that is associated with increased pain sensitivity to stimulus

One of my favourite clinical reasoning tools is the SIN analysis from Maitland. Lets not go too much into the Nature (type of pain), but severity (how much it currently hurts) and irritability (how long it hurts vs stimulus applied) really equal the modern concept of sensitivity. One of the key factors in ‘sensitivity’ is disproportionate stimulus and response (level and duration of pain or severity and irritability). This then would inform our clinical reasoning by reducing the stimulus or exercise dosage in line with current levels of sensitivity.

Rate of perceived exertion (RPE)

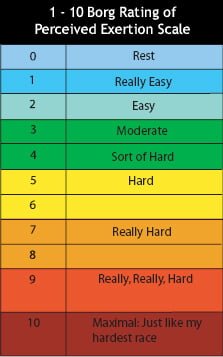

One of the measures I use to gauge dosage is effort level via the borg scale. This is far more subjective than using sets and reps in a traditional fixed sense and remember pain is a pretty subjective experience!

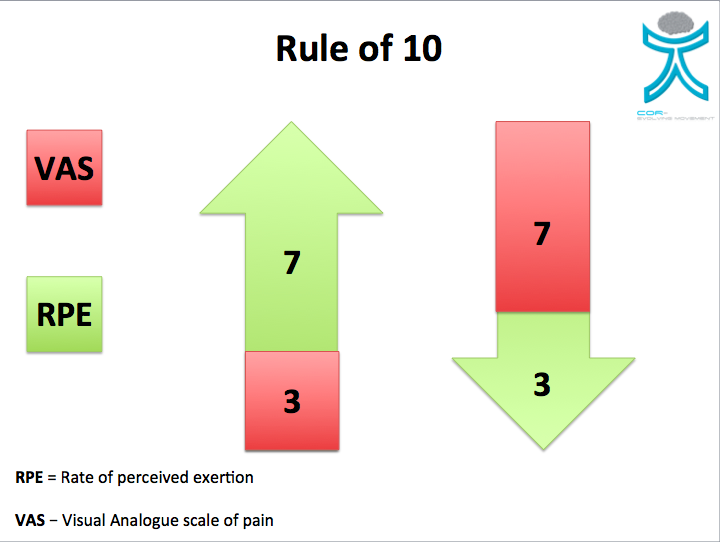

One of the hardest things is to keep our exercise dosing within tolerable limits in the beginning, or dose titration, when we have limited or no knowledge of our patients response. I tend to use a pain VAS (yes I know it’s a crap measure!) vs RPE. So if VAS is high then I make sure effort level is lower. I tend to find this keeps responses within tolerable limits, but of course not always.

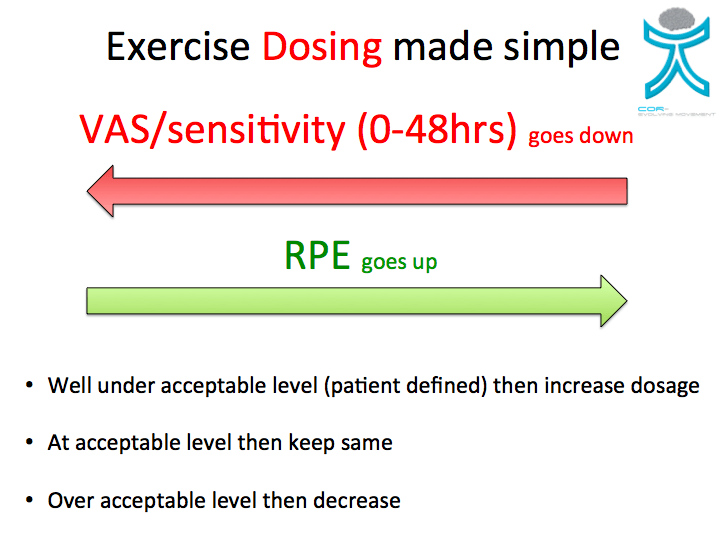

I call this the rule of 10, so both numbers add up to…..you guessed it 10! Example would be if pain is a VAS of 7 then I would keep RPE to a 3. If pain was low, say 3 on the VAS then I would maybe take the RPE up to 7.

But if you feel your patient is highly stressed, fearful or under slept then any of these things might have to be factored in to the dosage thought process if you want to keep the dosage within a tolerable response.

Monitor response to dose!

The most important thing is to monitor the response to the dose. Lets say we play it sensible and keep RPE low because of a higher VAS, and the patient finds it easily tolerable well then we know we can push it a bit harder and load em up. If we get an adverse reaction even though we kept the effort or load down then we may have to drop it even further.

Be OK in the grey

We will never really know what the dosage should be until we actually apply the dosage and then monitor the response. So its OK not know what’s going to happen, just use your ‘loaf of bread (head)’ and be OK with sometimes getting it wrong. Don’t panic, just adjust the dosage and educate that this is normal, it’s definitely not an exact science and often trial and error.

People will always want some kind of directions

One of the issues can be that people want to know how much to do and have some kind of direction. This usually end ups as 3x10 once a day (be honest, you have said this!) and I can understand why this is given as it is really quite difficult to be more specific. This is why explaining that it is a bit of trial and error with some good reasoning and also helping the patient to understand what a flair up might be/mean is important.

Conclusion

- We currently don’t have an exercise dosage for pain

- Pain does not respond consistently to current dosing parameters

- There are other therapeutic targets apart from physical aspects

- Exercise data does not support current dosing ideas in rehab

- Think about the current state of the patient with regards to dosing levels

- Use clinical reasoning

- Be OK in the grey

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!