After ‘pain science’ and ‘biopsychosocial’ the latest buzz word on our horizon seems to be ‘patient centred care’ or PCC for short.

Now for a buzzword it is pretty poorly defined and we don’t really have a strict description, but I think PCC is really how we should be implementing the BioPsychoSocial (BPS) model and what the BPS model was really meant to be about rather than the more pain focused version we have today.

This blog aims to focus on how we might apply PCC in the context of an active approach to treatment but don’t be surprised if it meanders off course a bit.

Patient or person?

Most of the available literature in this area discusses “patient centred care” but I much prefer “person” centred care as it turns the patient well ….into a person and a much more ‘real’ entity in a two way relationship.

The term ‘patient’ has long been open to discussion and this is an interesting read on the subject and I picked out a couple of quotes.

“Do we need a new word for patients?”

“Patient comes from the Latin “patiens,” from “patior,” to suffer or bear. The patient, in this language, is truly passive—bearing whatever suffering is necessary and tolerating patiently the interventions of the outside expert”

“An unequal relationship between the user of healthcare services and the provider”

These are interesting perspectives that highlights the potential perspective of the ‘patient’ as a passive recipient to be told what to do and without concern for them as an individual. After all tissues and pathologies really don’t care how they are treated so why the need to worry about it?

What actually is PCC?

Maybe by definition PCC is tough to define for all? What is person centred for one may not be for another, but there do appear to be some broad themes and ideas that can be discussed.

Patient (person) centred care has previously been defined as:

"willingness to become involved in the full range of difficulties patients bring to their doctors, and not just their biomedical problems" – Stewart 1995

"the physician tries to enter the patient's world, to see the illness through the patient's eyes'' McWhinney 1989

“Two person medicine (rather than one person)” – Balint e al 1993

(Quotes in Mead et al 2000)

For me, a good start for PCC is not to see the therapist or technique or method or exercise as the star of the show. It’s about the PERSON that really needs our help. That does not mean fanfares, razzmatazz and pedestals, it really means that we try to think about what THIS person in front of me needs, what is it like to walk a mile THEIR shoes?

Another very simple way to look at it is, how would YOU like to be treated?

Mead et al in “Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature” defined 5 key aspects of a “patient centredness”

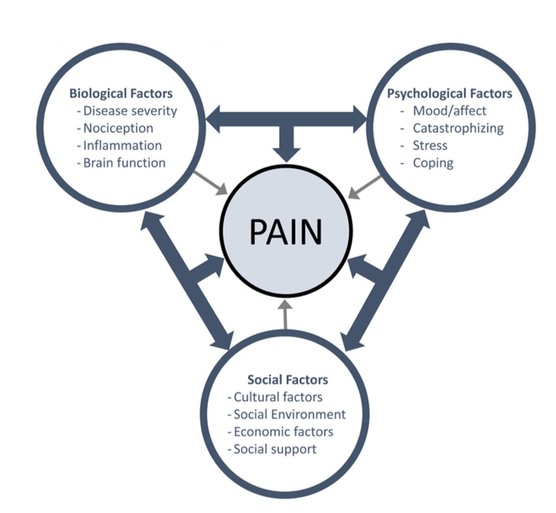

- The biopsychosocial perspective (the patients life)

- The patient as a person

- Shared power and responsibility

- Therapeutic alliance

- The doctor as a person (Personal qualities such as Humanness)

Wijma et al explored “Patient-centeredness in physiotherapy: What does it entail?”

They defined PCC as

“Patient centeredness in physiotherapy entails the characteristics of offering an individualized treatment, continuous communication (verbal and non-verbal), education during all aspects of treatment, working with patient-defined goals, a treatment in which the patient is supported and empowered, and a physiotherapist with patient-centered social skills, confidence, and knowledge”

What PCC is NOT

There are some criticisms of PCC that seem to centre around the idea of consumer driven healthcare and doing ‘whatever someone wants you to do’. Maybe the idea of ‘shared decision making’, intrinsic to PCC, seems to open up this idea of consumer healthcare for some.

These discussions are often dominated by the type of treatment and the application of more passive modalities and we really need to guard against this reductionist perspective of PCC.

Rather than MAKING the decision based on someone’s preference, PCC instead really should be about people being involved in decisions, a key part of PCC, and this should reflect the best information around treatment that we have available and frank and honest conversations around the best course of action. Not simply “what treatment do you want”.

Makoul & Clayman in “An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters” discuss a number of steps involved with shared decision making

- Define or explain problem

- Present options

- Discuss pros and cons (benefits/risks/costs)

- Assess patients’ values or preferences

- Discuss patient ability or self- efficacy

- Provide doctor knowledge or recommendations

- Check or clarify understanding

- Make or explicitly defer decision

- Arrange follow-up

What do people really want?

That leads us nicely into “what DO people want” and this does NOT seem to revolve around their favourite treatment type.

PCC is perhaps thinking about what healthcare can do for the end user, the person rather than how do they fit into the broader healthcare world. What better way is there to do that than ask them : ).

The increase in qualitative research is fantastic and really helps us understand what people think, feel and ultimately need.

This is a really interesting paper regarding a two person perspective in back pain Listen to me, tell me': a qualitative study of partnership in care for people with non-specific chronic low back pain

The authors here identified some key areas.

Partnership with practitioner

“All participants expressed the need for mutual enquiry, problem-solving, negotiation and renegotiation between care-provider and care-seeker to establish mutual therapeutic goals “

‘Ask me’

“All participants reported that engagement with their health care-provider improved if they were explicitly asked for their opinions and goals.”

'Understand me'

“Consideration of life circumstances and preferences was important to all participants in developing therapeutic partnerships and optimising exercise outcomes”

‘Listen to me’

‘Explain it so I can understand’ – Valuing competent and empathetic listener

I know my own body - Participants framed the ability to ‘know your own body’ as empowering

This sentence particularly resonated with me however

“Tension existed between patients’ wanting a genuine voice in the partnership and them wanting a care-provider to give explicit diagnosis and best management instruction”

Does It matter?

A question I often hear asked about person centred care is does PCC actually improve ‘outcomes’? I suppose my response would be does the effect of PPC on outcomes actually matter and which outcomes are we discussing?

Although we know that contextual factors have an affect on outcomes we don't know if PCC specificaly improves the most common outcome measures , but in my opinion it is the RIGHT way to treat other people regardless of if it changes pain, function or whatever. Although we don’t really have much data currently, my biases say for many it would make a difference, if not to common outcome measure then to the persons experience in healthcare (which might be an outcome measure in itself).

The application of PCC

Maybe we should NOT see a person centred approach to activity/movement/exercise just about the type of exercise or the sets and reps. Instead it’s about all those things AROUND the moving as well and I will focus mostly on these (you can retain your exercise bias : )

Starting with the end in mind

Unless we define what recovery might look or feel like it is probably hard for anyone to know if they are actually getting there. Really the role of the therapist should be to see where someone wants to get to, where they are currently and then help them bridge that gap.

The best place to start might be with the end in mind and this first and foremost really involves listening. Listening and understanding, is in my opinion the real essence of PCC but many people don’t feel that this always happens in their HealthCare experiences.

This short excerpt is from the excellent “From “Non‐encounters” to autonomic agency. Conceptions of patients with low back pain about their encounters in the health care system"

Holopainen 2018

“Patients felt that they were not being heard. They felt that the encounters were expert driven, and the HCP interrupted them and dismissed what they had to say, without listening to their wishes and opinions”

We also have to acknowledge that for some who have had pain for a long time this process of defining goals or recovery can be really tough. It’s often difficult to see outside of the pain and suffering to have a sense of what ‘life’ actually looks and feels like again.

“Patients identified the effects of pain on their lives. They reported that their circle of life had shrunk and they had given up doing things they used to enjoy” - Holopainen 2018

I try to highlight to people that they are not just moving for the sake of moving (although this can be a positive thing), we are moving to get further towards valued activities and goals that we have discussed and hopefully this can tap into people’s intrinsic motivation.

A big problem, IMO, with goals is that we can measure their success via their effects on more generic measures such as pain or function (certainly in research around physical therapies).

We have a wonderfully personal and specific thing, the goal, and we should actually measure the success of a goal by achieving……the goal! If that involves changes in pain then of course with a person centred approach we have to involve pain in the goal. But we might have no changes in pain (our outcome measure) but reach a valued goal that has a huge effect on someone’s quality of life and may not always be captured by the more generic measures.

I do believe that the ‘WHY’ behind action has to be driven by the person. So much of what happens in therapy is driven by the biases of therapists about the best way to get people pain free or functioning better.

Maybe the ‘methods’ employed often fit better with the identity and values of the therapist rather than the patient?

Shared decisions and responsibilities

As we discussed earlier, PCC and shared decision making is not just doing what someone wants. We need to present the best available information and our professional opinion on the best course of action to properly inform decision making.

Autonomy has been shown to be have an influence on exercise outcomes "Autonomy: A Missing Ingredient of a Successful Program?" . Perhaps some autonomy and choice might lead to better ‘bonding’ with exercise in rehab?

As there are a whole bunch of ways to exercise, move and load it should be not to hard to present a number of options and allow people some choice on the best way forward. Equally it is a therapists responsibility to give their opinion about the best course of action that they think will ‘fit’ the person based on the best data and a sprinkle of experience.

Laying out each others responsibilities in the process is an important step. I always say I am here to guide and help but you have to go and do it and believe in it for it to work. I believe we need accountability towards each other sometimes.

Planning

This for me really is true biopsychosocialism.

We are all people ‘embedded’ in the world with work, family and social pressures. One of the best ways to implement a BPS perspective is to realise that any movement/exercise plan is not going to come at ‘no cost’ in terms of time, effort and sacrificing something else.

People don’t just need a something to do, they also need a plan to be able to do it. A destination is great but we also need a path to get there.

How many things do you never quite get around to doing because you don’t have a clear time, place and structure to get it done?

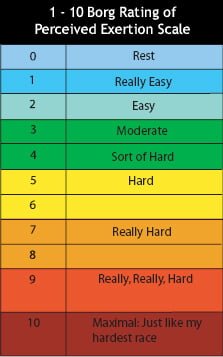

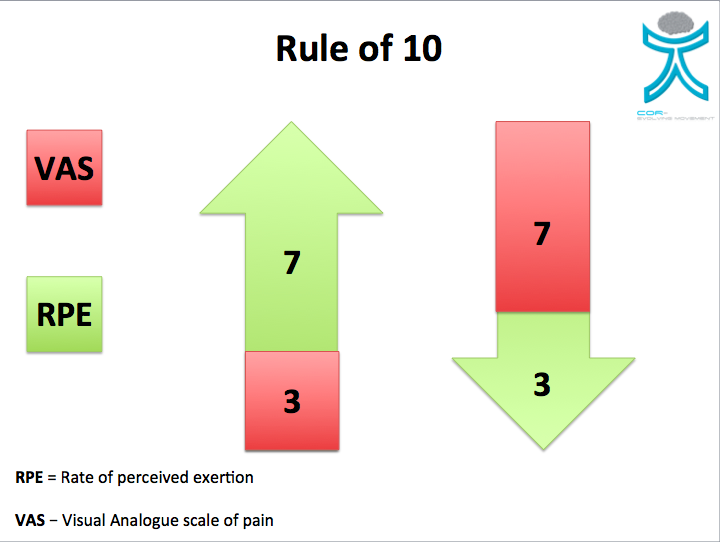

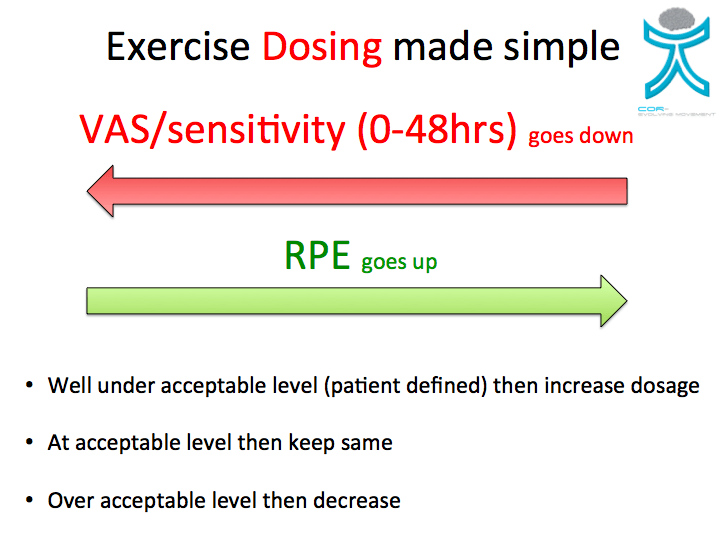

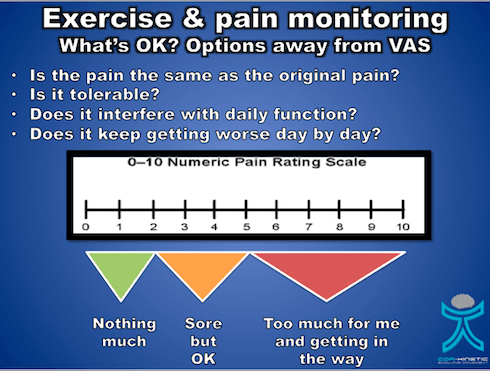

When’s the best time to do some exercise? Before or after work. How much is OK? What should it feel like? Do they have the required information to facilitate doing it?

Another passage from “From'Non‐encounters' to autonomic agency” highlights this.

“A lack of written instruction prevented them from doing prescribed exercises because they were unsure of what they were supposed to do”

Helping people to navigate their own individual social environments is also a beneficial way to help. We cannot often modify many ‘social’ things but we can help people understand and navigate them better. For example, how might someone access community support with getting more active? Are there free or low cost resources that they can use? Are there support groups or family members or friends that might be able to help.

Acting as a guide rather than healer can be really helpful for many!

Support & motivation

Picking someone’s exercise form apart or highlighting some kind of movement dysfunction really is the opposite of PCC. It shows a complete disregard for how that might make someone else feel and how that might impact on their behaviours. But I suppose if you feel you are just dealing with a pathology then why should that matter?

We could say that view is quite the opposite to walking a mile in someone else’s shoes.

Perhaps we can think about how we might lift someone up rather than pick them apart. Think about highlighting strengths and positives. We entirely underestimate the power of motivation and optimism in healthcare in my opinion. This is a fundamental part of the role of the coach or trainer in the world of fitness but has been lost in the translation of exercise to the world of medicine.

People even say this themselves!

“patients reported that they needed someone to push them, like a personal trainer” - Holopainen 2018

Conclusion

- Person centred care is defined by the person

- PCC is not just giving people what they want

- People are people not just patients (passive recipients)

- Think about “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes”

- Think more about shared decisions (within evidence base)

- Start with the end in mind, tie into valued activities

- Help people navigate their ‘world’

- Build people up rather than knock them down