The world of the science of pain or ‘pain science’ as its better known can definitely be a polarising topic when it gets discussed. These recent commentaries twitter/social media debates really highlighted this.

The truth about pain science, exercise and movement

The REAL Truth About Pain Science and Body Mechanics: A Response to Criticism

P.s the second one is better - Todd Hargrove is a great writer ; )

I would like to point out that I am by no means a pain researcher and really just a lowly blogger and clinician. It has been suggested this makes my opinions less valid and I am OK with that. So you have been warned!

Before we get into it there are two points I would like to make.

Firstly, the importance of understanding more about pain, from both a clinical standpoint and also a patient perspective should be highlighted. There can be great value for everybody in this area but one that is still evolving and has more to it than one or two dominant voices.

Secondly, pain can be seen a bit as a ‘special interest’ area. However if someone is working with those in pain and has not received some education on the current concepts around pain, at least to some degree, then a parallel maybe like being a chef who does not know much about the ingredients they cook with! The science of pain is one of the primary areas that clinicians, and anybody working with people in pain, should have some proficiency in.

Stuck on the Biological?

The term biopsychosocial gets thrown around a lot in healthcare. In my opinion there is no more important place for a BPS perspective than when it comes to our understanding of pain. It could be argued however, that the current dominant views and messages within ‘pain science’ in many regards have not really moved beyond the biological.

I would like to say explicitly the point of the this piece is not to say ditch the biological but instead consider that this might be insufficient to truly understand pain and its ramifications on peoples lives. There are also clinicians already advocating for this and combining both aspects.

The vast majority of the information and slogans we have about pain are specifically focused on the biology and anatomy, and the education mainly is grounded in these elements. Although in fairness the intention maybe that this biological message has an effect beyond biology and into behaviour, but the focus seems to be less on the behavioural aspect itself.

The most important message to come from this might be that:

"Hurt does not equal harm"So that the sensation and its magnitude, severity or however you want to describe it, does not have an ‘isomorphic’ (fancy way of saying simple, direct or 1 to 1) relationship with tissue damage. For many this has been an informative and empowering message but for others may not resonate with their pain experience in the same way.

If we think about the words used to discuss pain such as alarms, nerves, brains, sensors and nociception, they really relate mostly to biology and the stimulus and response process, or essentially the SENSATION of pain. It could be said that the information seems to be of more primary importance than the person it is being applied to.

Pain does not just have a sensory-discriminative aspect but also the affective-motivational one too that can be equally, and for some maybe more, problematic. The lived experience is more than just the sensation that we feel.

These are two interesting papers that discuss different perspectives on pain.

The sensory-discriminative and affective-motivational aspects of pain

Pain as metaphor: Metaphor and medicine

It might be that I am going to be accused of over complicating all this, and whilst there are simple messages that could have a positive impact, there is also an often-made point in the pain world that oversimplification has led to the discussion of ‘pain pathways’ and ‘pain receptors’ that are rightly pointed out as problematic for the understanding of pain.

So to think about pain as only a sensation or an ‘alarm’ may also be a touch incomplete when we view it outside of the biological and move into the psychological and social realms, perhaps this is a simplification of a complex multi dimensional problem? Maybe it cannot be conceptualised into one sentence such as “pain is protection” or “pain is an alarm”. While we cannot exclude the biological aspect of the pain experience, and we should not go down the the baby and bathwater route, the question is, is a biological perspective and explanation sufficient to fully explain how pain impacts on lives? I personally do not believe in many cases it is.

We seem to be really good at talking about the sensation, how it comes about and the biological processes involved, maybe we are not so proficient at exploring and explaining how this sensation affects lives, emotions and motivation and the overall unique individual experience that we might consider as the wider psychological and social impact.

Looking more at pain through a BioPsychoSocial lens

The real transformation in pain knowledge moving forward and building on the great work already done, from both a clinician and a patient perspective, I believe may come in understanding the impact on the psychological and social aspects of the human experience. Disability and suffering could be described as social aspects of the pain experience rather than a part of the biological ‘alarm’ system.

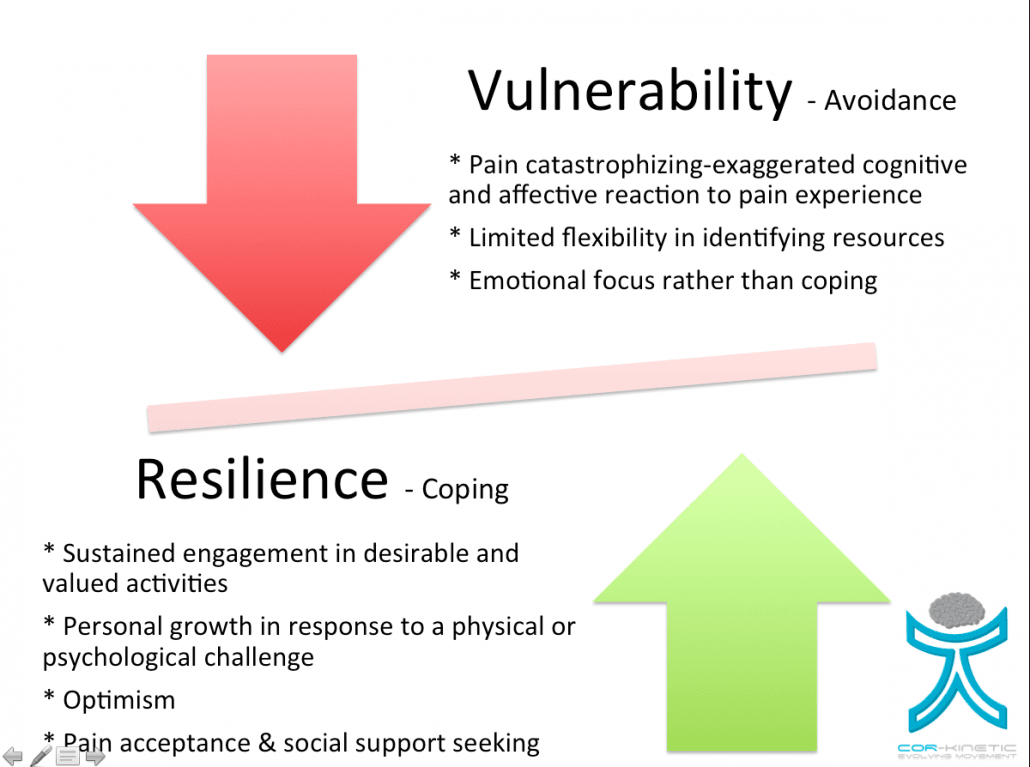

That pain is normal and occurs often is a key ‘pain science’ message. What differentiates those that do not develop persistent pain and those that are also able to live well with persistent pain from those that are most negatively impacted by pain?

It appears that the people worst affected by pain are perhaps not affected by an increase in the intensity of the sensation but instead by how much pain impacts on their lives as a whole, the ability to work or interact socially and integrate with society as a whole in a positive way. Now the interpretation of the sensation of course will be part of that but by no means all of it. Pain may have many meanings beyond just damage. Getting to this meaning and giving information that relates to that can be key.

This fits with Engels wider BPS with biological aspects being at the centre but having much wider ramifications right up to a societal level.

BPS factors

We perhaps also use wider BPS factors, sleep, stress, beliefs etc more to explain the increase or decrease in the sensation and sensitivity, so essentially contributors to pain.

The idea that the sensation of pain is a primary concern for patients has already been called into question with disability seemingly more important than pain intensity.

Factors defining care-seeking in low back pain – A meta-analysis of population based surveys

Wider BPS factors can, often be studied in relation to ‘pain sensitivity’ or ‘tolerance’. The increase or decrease in response to a prolonged or painful stimulus can be discussed with relation to the sensation or an increase in ‘sensitivity’. The focus seems to be more on the effect of these factors on pain rather than the effect of these factors on the person and their quality of life. Shouldn't we be doing both?

Lets take sleep as an example.

Sleep has a bi directional relationship with pain and it is unclear which is the chicken and which is the egg. Poor sleep can really affect my job, my social interaction and quality of life, instead we can focus on this aspect to explain the sensation and then as a modulator of the sensation.

This has also been conceptualised as “pain is telling us something is wrong, we just don’t know what” with regards to a stress or ‘allostatic’ load view of pain.

So whilst pain is often described as being inaccurate in reporting on tissue damage, pain can be seen as reporting more accurately on wider factors that have been associated with pain. Although it does not seem it can tell us exactly what, so insert anything here, to blame for pain.

I will be honest in that I struggle with this concept and have also realised that I have maybe got myself into a mental pickle : ).

In one sense we should see the ‘alarm’ as perhaps being something to not take so much notice of, the idea of being ‘time contingent’ rather than ‘pain contingent’ with exercise for example. Whilst when pain is ‘reporting’ on psychosocial stressors it should be taken much MORE notice of.

It could be, and likely is, that PS factors might be no more isomorphic with pain than tissue damage and our pain experiences to the same ‘stressors’ will remain highly individual. But this is taking a sensation dominant view of course and this is exactly what I am arguing against here.

We also talk about the biology in a very general way. It’s the same for everybody essentially, but does this generic biology result in the same experience? I do not personally believe so. It is getting from this biology to the lived experience that may prove tricky.

The burning question is how much biology do I need to get across and how much does mostly focusing on the biology help? Of course that answer may prove to be individual rather than a generic singular solution.

A common argument for the alarm system is evolutionary based

One of the arguments for the current view of pain is based in an evolutionary perspective. So the ideas of pain as an ‘alarm’ or ‘protection’ look at pain from the need for basic survival.

When we look at pain from a BPS perspective perhaps some of the ideas of protection do not fit as well as when we view them from a more basic evolutionary perspective.

At the most basic level nociception, I think, can be conceptualised as an alarm. The network of a high threshold detection system falls nicely into the bracket of an alarm. But we also know that nociception does not simply equate to pain (remember the oversimplification thing). Pain could arise with the further analysis, or maybe lack of analysis potentially, of the alarm system. So is pain actually our reaction to the alarm?

But I digress.

This conceptualisation of pain maybe focuses less on the impact of pain at a wider level. Whilst there is a ton of research in the psychological domain and some in the social, I don’t think it has really made its way into the most dominant pain messages that are discussed and used with patients. A multi dimensional view of pain does not JUST consider the role of biology and threat but also the wider impact of pain across the BPS spectrum and also the bi-directionality of this.

The alarm conceptualisation does not really give the picture of how pain effects human beings, their psyche’s and the wider societal effects. Can we explain away disability, suffering and many of the other impacts of pain on our psychological and social functioning as the singular role of an alarm?

Maybe our biology has not kept pace with the changes in our psychological and social environments? The simple alarm system has not adapted to the meanings and emotions we give to it and the wider ramifications on our functioning in society?

What are future directions?

Now, in my opinion, it seems the current dominant approaches of pain science education focus on the biology and slowly works its way out to the psychological and social. Perhaps we should start at a broader point on the effects of pain on life and work our way back down to the biology if required?

Seek first to build rapport and understand the person and their situation before explaining it.

We can talk about pain with people and for some it makes a huge difference. Not for all however and as per all interventions will have individual effects.

Maybe there is not a universal way to explain pain? There is no flash card set or single conceptualisation that is correct for every experience of pain.

Something I have discussed for a while is making it relevant to the person you are working with. Helping people make sense of THEIR experience and THEIR pain may make it more relevant.

Don’t just apply information to people and expect to their behaviour to change. Define behaviour change and use specific information and experiential approaches to specifically change behaviour, then monitor closely if this has been effective.