The perspective that the body is an interconnected unit that displays regional interdependence is a valuable one. That different parts interact in different ways during different activities and influence ROM (range of movement) in other areas of the movement chain should seem a fairly easy link to make when looking at the whole body during different context dependent movements. We often eschew the value of the integrated system in favour of the isolated joint/muscle model.

Read more

Posts

One of the key things to understanding how to view the body functionally specific is the biomechanics behind how we move.

A (simplified) understanding of biomechanics allows us to break down different functions to create authentic movement based techniques that create the right joint reactions for when we are training or treating our clients. After teaching a mentorship group last weekend some of Cor-Kinetic’s principles of biomechanics I thought I would write this blog post to help explain our process that has also been influenced by the teachings of the Gray institute.

Now the word biomechanics sounds a bit scary. If you have ever opened up a biomechanics book or journal then you will probably have had a similar reaction to me, which is one of amazement at the equations and symbols on offer!

(Apparently the biomechanics behind swimming!)

Instead in the process we use at Cor-Kinetic we are looking more at the movement of bones both in real space and in relation to each other. This relative movement of the bones creates specific joint reactions that in turn will have an affect on the attached muscles for an authentic reaction in the neuromuscularskeletal system as a whole.

The real key is in understanding that the real bone motion and relative joint motion can be different. So in essence we could have two bones both externally rotating in real space but the relative motion between the bones at the joint could be internal rotation. This hinges on the difference in speed between the two bones. Lets outline some of the key points below.

Proximal and Distal.

It is key to know which is the proximal and which is the distal bone at a joint.

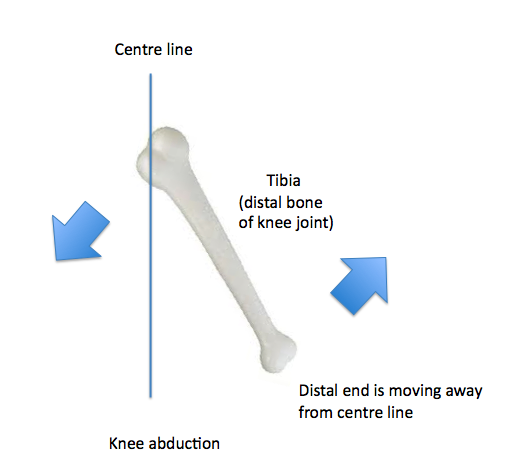

In the appendicular skeleton (extremities) the motion the DISTAL end of the DISTAL bone is going through RELATIVE to the PROXIMAL end determines joint motion. This means if the proximal end is moving towards the centre line in the frontal plane for example then the distal end will be moving away or abducting!

The distal point of the Axial skeleton is also known as the superior point. So now we look at the superior point to define joint motions at the axial skeleton.

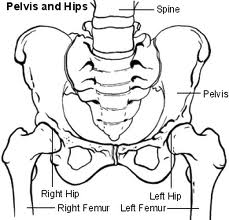

The proximal bone is the one that is closest to the centre of the body. Therefore the pelvis would be the most proximal bone of the body. The other bones are distal to it. That makes understanding the proximal and distal bones of the hip joint easy as the pelvis is always proximal. At the knee the femur would be the proximal bone to the distal tibia.

The motion of the pelvis is also determined from a different point. Rather than the distal end (because both are!) we look at the relative movement between the ASIS and PSIS. Anterior rotation would be the counter-clockwise rotation of the ASIS so the PSIS would be superior to the ASIS.

The same counter-clockwise rotation as we see from the tibia would be described as posterior rotation because the distal end has rotated towards the posterior. This can sometimes be confusing because both the tibia and pelvis bones are going through the same rotation but one is described as anterior and the other posterior!

Relative speed.

The relative speed of the two joints is also critical to determining the relative joint motion.

It is important to now know which bone is moving faster as this will help to determine the relative joint motion. The general rule is that the closer the bone to the driver of motion the faster it will be going. This is because of the dissipation of force. As an example, a foot driven motion will generally mean the distal bone of the lower limb will be moving faster. So at the knee the tibia will be driving faster than the femur. If we were to hit a tennis shot however the proximal femur would be closer to the driver of the hand meaning it will be moving faster. At the elbow however the distal radius would be closer to the hand meaning it would be driving faster than the more proximal humorous. So we need to know the driver and which of the bones that comprise the joint we are looking at is closer to the driver.

There are 3 real ways a joint can move in function (and two more less functional to make 5). This would be proximal and distal moving in the same direction, proximal moving faster. Proximal and distal moving in the same direction, distal moving faster and then proximal and distal moving in opposite directions. This would be either towards or away from each other as if we view a clock face movement towards each other would mean one was moving clockwise and the other counter clockwise this would be the same when moving away from each other also!

This is all very easy when the distal bone is moving faster as the real bone motion and relative joint motion will be the same. The confusion comes in when the proximal bone is driving faster than the distal in the same direction. In this case the relative joint motion will be the opposite to that of the proximal bone. An example in the transverse plane would be at the hip in the back leg of gait. Both the real bone motion of pelvis and femur is rotating in the same direction, externally. However because the proximal is rotating faster the relative joint motion is internal rotation. The easiest way I find is to put my fists on top of each other. I then rotate the proximal bone in the direction it is rotating, in this case external. I then rotate the bottom hand in the opposite (what determines the joint motion) and this is internal! The transverse plane can be easier to understand sometimes because the whole bone will be rotating in the same direction rather than the proximal end one way and the distal end the other!

One movement that can sometimes be confusing is abduction of the knee. This is because the largest motion is from the proximal end going towards the mid-line, rotating around the axis that runs posterior to anterior. But if we follow the rule of naming the joint motion from what the distal end of the distal bone is doing relative to the proximal end, then it is moving away from the centre line of the body or abducting! Easy when you know the rules!!

Check out www.cor-kinetic.com for more information on our courses.

As always this is an example of our thought process rather than a defined way that things have to be done in an academic sense! We hope it helps!

I have read a lot of stuff on movement screens recently and specific "functional tests" such as overhead squats and single leg squats. People both extolling their virtues and others maybe less sure about their validity.

I thought I might chime in with my thoughts on these "screens". Firstly part of the problem is we are trying to shoe horn function into a handful of assessments. Given the incalculable number of functions this is a pretty tall order. Another problem is that we are trying to 'define' Peoples function. This has always been the problem with 'functional' training, trainers tend to define the clients function rather than the other way round. A more successful approach, although less easy, is to have a thought process that allows us to understand the biomechanics behind someones function and be able to design a test to tell us how well someone interacts with their functional activity. At Cor-kinetic this forms a cornerstone or principle of how we approach the body and teach people to approach the body.

So are you testing the test? Or are you testing someones functional needs? That is a question you have to ask yourself! If the test has nothing to do with the needs of the client or player then what validity does the answer have? We are simply testing a test.

All movement is a specific skill. Many sporting movements are very specific skills honed over a number of years. Is a poor test on a movement we have not practiced just poor skill at the movement as we have spent no time refining it? Are the improvements in the movement skill based? If so then would it not be better to spend the time practicing a skill that we really need for our sport? These are all questions we need to ask.

As movement patterns live in the brain and we have between 100-120 billion neurons each with around 10,000 connections each I am pretty sure we have the neural real estate to hold more than a handful of movements that define how we function.

Does a tennis look like rugby? If not then we need to find a way to screen them specifically.

The single leg squat test does go a little way to incorporating a functional thought process. The fact that a person during gait spends between 50-85% on a single leg depending who you listen too has a sprinkling of specificity. I think more towards the first figure for walking and more towards the second figure for running! However the amount we squat during walking gait would be minimal.

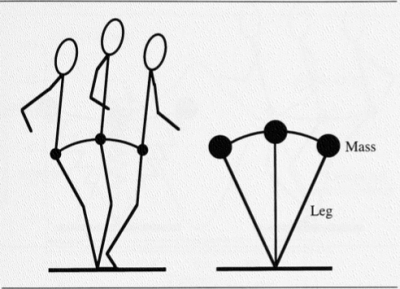

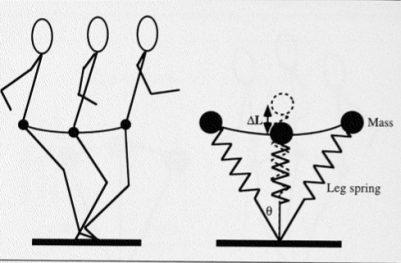

This is the inverse pendulum model of human walking gait, this means we are able to be efficient and use gravity to transfer our COM (centre of mass). This is in opposition to the spring mass model of running. The aim of walking gait is to not overly squat and lower our COM. (Farley 1998)

So a single leg squat maybe more 'functional' for running but not walking gait. Although the depth of the squat may still not be large. We can see the variation in function here and a single test to define our 'functionality' may be of limited value. A much more valid process may be to understand the variation in function of the client stood before me.

The major factor in both functions (walking and running) is being able to effectively move our COM. The ability to translate as well as rotate is a massive component of human movement. Nearly all 'functional' tests seem to assess our ability to move in the vertical component of the sagittal plane rather than the horizontal which is at least as important if we ever want to get any where. The art of transferring and controlling our COM dynamically should be a principle part of any 'functional' testing screen or protocol.

This is something that the S/L squat does not tell us but is one of the most important 'functional' tests we can have. Also would a more effective adaptation to a S/L test to find out how our pelvis is able to rotate over our femur creating relative IR at the hip whilst in a S/L stance?? This would be more 'functional' for both walking and running. The stability we crave in a S/L stance maybe generated through eccentric tension of the numerous external rotators and adductors (many of which are lengthen in IR)! Without the pelvic rotation this stability could be compromised, so testing stability without pelvic rotation on a S/L for gait maybe a bit like a driving test with 3 wheels!!! Function is specific and if we want to be 'functional' we must learn to be more specific also.

An overhead squat test is another 'functional' test and very rarely in functional activity do we do things bilaterally or over head for that matter!

If we go back to the pretty universal function of gait, we can see that the two arms are doing different things. One is flexing, one extending. One externally rotating, one internally. This means that the scapulae will also be doing different things. elevating and depressing, retracting and protracting. In fact any function which involves rotation (pretty much all of them!) this will be occurring at the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints. Can a test that fails to take any of this into account be reliable for predicting any movement pattern dysfunction in the body away from a single plane overhead squat?? In everyday function we rarely squat from a contrived position defined by someone else. Squat down to do the gardening or get something from the fridge I guarantee it will not be in the pelvic neutral, toe out and linear fashion we do in the gym. To assess and train like this and define it as 'functional' may not be accurate in both thought process and application. The variation in foot position, and therefore hip position, in all three planes in functional squatting is huge. Dysfunction or pain could be occur away from this one contrived position and a thought process that allows us to test a wider variety of positions in a movement may give us more information.

Lastly muscular range in one plane of motion may be naturally mitigated when three-dimensional tensile or compressive force is acting on the fibres. Simply a structure may not be able gain as much length in one plane when also being pulled in another direction or plane. So a test that only tests a single plane at a time may also give information not consistent with three-dimensional functional muscle movement. This is similar to single plane force production (isolated) not being applicable in a three dimension environment where force has to balance across three planes.

As always this is my opinion on a complicated subject that has no definitive answer, only more questions!!!

So I have not blogged for a while. It feels like I have been here, there and everywhere teaching in November. From New York to the Manz fitness conference in Portugal and more locally in the UK.

In this blog I want to look at a more functional approach to the concept of strength or maybe more importantly force production during function. One way of defining strength, as always there will be different definitions, would be the ability to move an external resistance or generate force to overcome a load (and its inertia if we are being consistent with Newton) . Generally in the gym this would be a weight.

Now with a weight it is very easy to quantify the fact we are moving a larger external resistance or mass. In fact it usually says it on the side in a numerical form. The question we have to ask is does this make us better at force production within our function (if that is what we want of course)??

Lets go back to our good friend Newton. His second law of acceleration defines force production or F=MA. This is force = Mass and Acceleration. This equation tells us that force can be produced in two distinct ways, M over A or A over M. As we tend not to walk around with Newton meters to measure force it is much easier to just quantify the mass element of this equation. So we look at M (mass) over A (acceleration) as a simple way of measuring our ability to produce force. The question is are most sports high external resistance and therefore M over A or lower external resistance and more A over M. This is a harder question to determine but if we look at a couple of sports this might give us an answer. Sports such as tennis and football (soccer) would have a lower external resistance and rely much more on changes in velocity to generate force or A over M. This would also be true of throwing a punch or ball. In these circumstances would ability to move large masses help us??

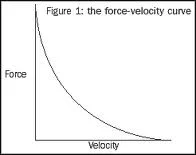

If we look at the Hill curve (1953), which is the hyperbolic force-velocity curve, this implies that velocity of muscular contraction is inversely proportionate to load. We can see that large muscular force cannot be exerted in rapid movements, as we would see in weight lifting, that would be associated with changes in velocity or A over M to generate force .

So do we need to be strong to be good at our sport?? One perspective is that the greater someones strength (M over A) or hypertrophy and physique the better. Although I think this is often not the case in the sporting arena as we see amazing performances by people on a regular basis who do not fit this bill. It maybe that within a more functional context a sub classification of speed strength maybe more applicable. We would define this as the ability to execute a movement against a small resistance with a high velocity.

Speed and intensity of movement will recruit the fast twitch muscle fibres associated with maximal effort. These fibres are recruited as per force needed. As previously highlighted this force can increase A over M as much as M over A! So do we need to be specific in the way we recruit these FT fibres if we can recruit them also M over A? Moffroid & Whipple (1970) found that there was little transfer effect from low velocity training to high velocity training, couple this with the Hill curve data that force decreases with the velocity of contraction, it would appear that specificity plays a role in increasing applicable force.

So we need to specific in the way we produce force. So then what about the position this force is produced from in terms of movement or motor pattern? By using set classic gym based strength exercises for strength in a wide variety of sports, this would indicate strength is perceived as generic in terms of position rather than specific. However research does not support this assumption. Verkhoshansky (1968) sees the kinesiological pattern as important in special strength training and the patterns of force production depending on a specific neuromuscular process. Sale and MacDougall (1981) also see "Increased performance is primarily a result of neuromuscular skill". They also comment "increased strength is apparent only when measured against the same types of movements used in training". This all seems to point to the fact that specific function related movement patterns and their mastery is important in increasing our force production and performance. Bompa (2000) says “Strength adaptations are angle specific and thus all possible angles must be utilized". Lifters have known this for a long time as they often change angles through inclines and declines, however they rarely use planes other than the sagittal. Different angles, as well as interactions with different planes of movement, occur in different functions and sports. This means that function related angles, planes and movement patterns could be important in increasing force production and strength in a classic sense if required.

We also cannot replicate maximal forces produced in a single plane of movement during non function related fixed positions when in dynamic upright function. Force would have to balanced across all 3 planes of motion (as function is three dimensional) and also relate to three dimensional external forces acting on the body. This would also diminish applicability of non specific strength training to functional performance.

The body has found a unique way of controlling and harnessing external force for force production and energy and information efficiency. This would be the load to explode of eccentric before concentric muscular actions involved in the stretch shorten cycle. The vast majority of functions use this process from hitting or throwing a ball to standing up from a chair (we flex forward before extending). This action of creating tensile force on the muscle elicits the myotatic reflex for neurological muscular activation vital in functional force production and also storage and recoil of kinetic energy from the more passive myofascial structures such as tendons. We know that energy conservation is vital to prolonged force production involved in sporting endurance. As energy decreases so does skill and likely hood of injury.

As always this is purely my personal opinion on the concept of strength. It is a different view from the traditional paradigm and may not be shared by strength purists. However differing opinions are vital to understanding the complexities of the human body we all love and cherish!

Ben Cormack

I have read a few blogs recently on fascia. All of them giving a different perspective on what is a very prevalent topic at the moment.

One was based around the significance of fascial contraction and the biomechanical influence it could exert on the body. This made me think of the a pair of articles and an audio presentation I wrote for PTontheNet. In these articles I posed the question "how would fascia contract".

As far as I am aware fascia seems to mainly afferent, sending information to the CNS, rather than being able to efferently regulate tension through the feedback loop of muscle spindles and motor units. So if fascia does actively contract then why and is an active biomechanical influence helpful??

Chemical contraction has been noted in vitro (out of the body) in rat fascia (schliep 2006). These changes in response to chemical factors were in this case due to calcium chloride, calcium being involved in both skeletal and smooth muscle contraction although in different ways.

I think the link between the biochemical and biomechanical is an important one. Stress creates significant biochemical changes in the body. Hormones associated with stress such as cortisol are also involved in energy regulation. The body in response to long term stressors and increased energy expenditure may choose to decrease movement to conserve energy. This could be looked at as another way of interpreting the law of energy conservation on a metabolic level!!

One way of decreasing movement could be to increase the stiffness of the body. Fascia in its various forms being ubiquitous in the body could certainly play a role in this longer term stiffness regulation that would require less instantaneous neurological control than involved in active muscle contraction.

Now this maybe good for the body on one level (energy), maybe not so good on another (movement). So the biomechanical impact of stiffness regulation for fascia may be detrimental for our movement, especially if it becomes a learned response of the body and becomes the 'default' tension even when under less stress as I believe can happen.

Some may argue that increased compression through contraction of fascia at the lumbar spine is helpful. However this may not be the case if the movement at our hips is also reduced. The ball and socket joint of the hip is designed to have a large movement potential especially in the transverse plane. If this motion is reduced, through fascial stiffness, more motion may have to come from the lumbar area to achieve function related movement. Lumbar rotation is limited (by facet orientation) to 5 degrees collectively in all the 5 vertebrae!!

This could be a recipe for increased articular surface compression if the superior segment rotation (driven by top down movement) is not in close sequence with inferior segment rotation. If both rotate similar amounts then less compression. If one is blocked then this will increase compressive force between the two segments. If we put our hands one in front of the other and rotate them together we feel less compression. Try moving one and keeping the other still, this will increase compression. If the pelvis is not able to rotate on the femur then the inferior lumbar segment closest to the hip will be blocked. This will lead to increased compressive forces and possibly also to pain!

It does however give an insight into why some people have chronic movement dysfunctions that cannot be treated by biomechanical intervention alone without looking at biochemical, nutritional or emotional factors.

I also think we overlook the passive role that fascial stiffness plays in the body. Is passive resistance to movement as important as active contraction?? I personally think so. Our passive stiffness controls the range, speed and energy consumption of our movement. This seems to be overlooked in a similar way to eccentric muscle contraction controlling our movement by decelerating our momentum and controlling forces.

The differing types of collagen contained in different fascia may give slightly different interactions with energy. Some stiffer varieties maybe able to store and return energy whilst others may exert their stiff properties before plastically deforming and having their shape reset by muscle force.

This model would be quicker and more energy efficient than active contraction, neurological or chemical. The force of the movement (hopefully) dictating the correct response of the tissue.

As always this is merely my simple opinion on a complex clinical subject. I have also tried to give a perspective using a functional movement context.

Ben!!

The hamstrings are one of the most misunderstood muscles in the body and the explanation of them shortening when we bend the knee or lengthening when we straighten the knee is a huge simplification. To also view them simply as a sagittal plane beast does a disservice to the power that they hold in other planes of movement.

The first question is why are there three and why do they attach in different places? The attachment of the biceps femoris on the lateral fibula straight away gives us control in the transverse plane. As the lower leg goes into internal rotation the hamstring is able to eccentrically control this motion. This is similar to the gluteal attachment on the femur that allows it to control hip internal rotation. If we look at the universal function of gait and how much of the gait cycle is spent in internal rotation, due to ground reaction and gravity, it becomes easy to understand why.

The semimembranosus and semitendinosus are on the medial side of the femur attaching into the pes anserinus and onto the medial tibia. From this position they will have much more control of external rotation of the lower limb, either femur on tibia or tibia on femur. If we look at the pathomechanics of ACL injuries for example, the ability to control real femoral internal rotation, thus creating relative external rotation at the knee, is hugely important. Add to this the eccentric control that these muscles will exert on valgusing of the knee, especially with its close proximity to the MCL, we can see the multi plane importance of having these two distinct portions of the hamstrings. In fact should we even lump them together as a single entity??

The might Gary Gray described them as the like the reins of a horse which is a pretty accurate description. This multi dimensional ability though is rarely noted.

The fibre arrangement remains fairly longitudinal in the sagittal plane. This gives the unique ability to control the range of movement through the other planes. Reduced ability for the fibres to move and lengthen in directions away from the fibre arrangement gives it an inherent stiffness to control motion. A function related example of this would be how the hamstrings can help control foot pronation through slowing down tibial motion in the frontal and transverse planes at the proximal end.

The fact that the pelvis and the tibia/fibula are both connected to the hamstrings mean that the hamstrings can lengthen when the knee is bent and shorten when the knee is straight. This is all dependent on which section is rotating faster, something that is key to a bi-articular muscle. This means that if the tibia is rotating forward faster than the pelvis then the hamstrings will lengthen. We see this in the front foot phase of gait. The tibia’s distal end is rotating posterior while the superior portion of the pelvis rotates anterior. The tibia closest to the ground has to deal with more force so is rotating quicker creating knee flexion but lengthening of the hamstrings. If the pelvis rotated faster we would spend a lot of time looking at the floor!!! Add into this the anterior translation of the femur due to gravity and connection to the tibia and we also get a lengthening force on the hamstrings at both the distal and proximal ends.

Equally during the up phase of a squat if the pelvis is rotating posterior faster than the anterior rotation of the distal section of the tibia then we will get shortening of the hamstrings, even though the knee is extending!

The two attachments of the hamstring can be important for understanding hamstring injury. Many times we see hamstring injuries as lower limb dominant. However a top down drive e.g. pelvis driven, can make a huge impact. If the hamstrings are already under a large amount of tension as we may see during swing phase (large hip flexion of swinging leg) of sprinting. Then any additional tension caused from movement of the head affecting the pelvis may be too much for the hamstrings to handle. This could be more sagittal plane tension or rotational tension from looking side to side.

In the video clip below we see Fernando Torres as he is sprinting for the ball.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d6rhDpELsSg]

He is looking behind him. This would create some posterior rotation at the pelvis. As we drive the leg (femur) up into hip flexion this posterior rotation would reduce force created through additional eccentric tension on the hamstring that is generated from the anterior rotation of the tibia of the swinging leg. The problem comes when the ball drops and his head comes forward creating more anterior rotation of the pelvis. Now the hamstrings are being lengthened in opposite directions from both attachments. Under extreme force such as sprinting this can cause the hamstring to close down to resist this extreme force. The tissue confused from a proprioceptive standpoint and unable to lengthen will be at far greater risk of being damaged.

So why is it important to know all this about the hamstring?? Well it helps us create an authentic strategy with which to treat and train the hamstring. If the hip or ankle lacks internal rotation and therefore does not allow the hamstrings to lengthen in the transverse plane, then by understanding this need for multi-plane flexibility, created in different ways, we can factor this into our programs or techniques we use.

Knee pain is very, very common. Although there are many types of knee pain affecting the various bursars, tendons and ligaments in that area, one of the most common is patellofemoral pain.

Rather than delve too deep into the minutia in this blog post it maybe much better to have a conceptual understanding of what is needed for successful patella femoral mechanics.

The patella is attached to the femur and tibia via the patella tendon. In fact it sits in the groove or Condyles that are both medial and lateral on both bones. This means that for successful movement of the patella, these grooves need to stay pretty close. A great way of describing it would be “in sequence”. Otherwise the patella can smash into the groove causing pain.

We have two pretty important bits of the body attached to these two bones. Namely the hip which attaches to the femur and the foot attaching to the tibia. That means the sequencing of the grooves can be affected by excessive movement or limitations in movement at either end, the hip or foot.

A common approach is to try to limit the movement at the hip and foot by tracking the knee in the sagittal plane, in effect reducing the variability of motion. The wondrous nature of a ball and socket joint is the huge freedom and variety of movement it gives us. In fact this freedom and variety could be described as tri plane. An attempted reduction of motion into the sagittal plane will reduce the load to the hip musculature that displays a distinct tri plane nature. Look at the glute and its oblique fibre orientation. Without frontal and transverse plane motion of the femur it will not work effectively. In fact the glute will control the femurs motion into adduction and internal rotation. Deviations away from the sagittal plane, that occur frequently in functional weight bearing movement, of knee valgus (femur adduction) and femoral internal rotation will need to be slowed by eccentric activation of the glute and hip musculature. This maintains the optimum sequencing between femur and tibia for healthy patellofemoral mechanics

Equally the operation of the foot will affect the sequencing of the tibia. This will also disrupt the patella in the groove. Using gait as an example (and universal function) a rearfoot or forefoot varus will have an acceleratory effect of the tibia following the foot into pronation, creating increased tibial internal rotation and abduction. The sequencing of pronation will also affect the sequencing of the patella femoral mechanics. Late rearfoot pronation will decrease the external rotation of the tibia that along with femoral external rotation keeps the grooves closely sequenced. In fact we may get opposite rotation of femur and tibia. The patella attached to both, as my friend Gary Gray says, “gets caught in the middle with no place to go’.

A lack of motion in sagittal plane such as ankle dorsi flexion may also increase pronation affecting the knee. This is why people may complain of feeling their knee more when using the stairs. Increased dorsi flexion is required when ascending or descending the stairs. If this dorsi flexion is not available at the talo-crural joint the body may use increased pronation at the Sub-talar and mid-tarsal joints to create more flexion. This increases the frontal and transverse plane forces on the tibia and therefore patella. So increasing the sagittal plane demand as traditional exercise aimed at dealing with patellofemoral mechanics does, may actually cause an increase in the motions that cause pain! An understanding of why dorsi flexion maybe limited could be a more successful approach rather than just try to force more sagittal plane knee motion!

Functional tri plane assessment of both of the hip and ankle are required to understand what maybe causing knee pain rather than generic one size fits all exercise. So many structural foot dysfunctions are present in the general population that without understanding functional biomechanics and structure we cannot effectively treat these problems. A knowledge of how the knee acts when weight bearing rather than just on a plinth is vital as tri plane motion occurs mainly when weight bearing.

Something that always confuses me is the dissociation between foot pronation and knee motion. We classify pronation as movement into dorsi flexion, abduction and eversion and is well documented. This will create tibial internal rotation following the talus. This tibial motion connected to the femur will create internal rotation of the knee. How then can the knee work as a simple hinge joint when weight bearing moving exclusively in the sagittal plane??? Equally the abduction of the tibia at the distal end will result in the proximal end falling in towards the midline of the body creating a valgus at the knee. Again how can we see the knee simply as a hinge???

It is vital that close association of both the femur and tibia occurs in all 3 planes for functional success. This means assessing the foot and ankle in weight bearing and dynamic positions! At Cor-kinetic we always use this thought process when dealing with these types of problems!

Being flexible has always been seen as a great thing. The more stretchy the better!! The ability to assume any number of crazy yoga poses at will.

Hypermobility however can present its own set of problems.

As we start to understand the body as an integrated unit that relies on the chain reaction of movement for its success, the more we realize that a certain level of tension is a good thing.

The body relies on the eccentric lengthening of muscles to create concentric shortening. All of this has to happen within optimal range and sequence. With a hypermobile person the pretension to create the transformation from one contraction type to another will now not occur in the optimal parameters.

An example of this chain reaction in gait would be of internal rotation of the hip and supination of the foot. As the stepping leg passes over the standing leg it creates relative internal rotation at the hip-joint. This internal rotation will create information and energy for the explode of external rotation of the leg. This also occurs because as the internal rotation runs out at the hip, the pelvis also drives the femur round with it. All this helps the foot to go through supination.

With the hypermobile person, the level of pretension is not there. This means that to get tension for proprioceptive information, energy and to drive the leg from above the pelvis will have to travel a hell of a lot further. If we look down at the foot, by the time it has taken for all the reactions to occur above the correct time for supination has passed. This may mean that the foots effect on the hip in terms of extension may also have passed. This leads to an ineffective gait cycle.

The increased elastic elongation of the muscle has swallowed any tension that may have been generated by the movement.

As we learn to walk as babies we can see the lack of pretension or stiffness regulation in their movement. As we become more effective our joint ranges become more controlled and our internal level of tension improves. This enables the effective transfer of energy and information and hence chain reaction biomechanics to occur.

Hypermobility has implications for energy consumption and speed of movement. Simply put the larger the joint and muscle range the more energy we dissipate as heat through the splitting of ATP. The larger the joint range the more time it takes to control.

If we see stability as control of movement, rather than the rigidity than the current ‘core stability” trend promotes, then hypermobility may not succeed. In fact rigidity maybe what the body uses for stability in lieu of controlled movement. This would be dysfunctional. Hypermobile joints will interfere with the correct sequence of motion that leads to pain-free movement. It may also force rigidity into other areas of the body to control overall range. This will also interfere with sequencing.

The lessons I have learned from my experiences of working with hypermobile people have always been to find the inevitable areas of rigidity that seem to appear. Also working within ranges that can generate tension in the system, many times this is best done weight-bearing and moving, as this will generates its own tension demands on the system.

Tension too much or too little will also have an effect on the pain receptors and their threshold. Certainly the more tension a rigid area is under the lower the activation threshold of the pain nerve endings becomes. Although I am not sure of the research into laxity and pain thresholds I would believe a step away from optimal might have some impact.

Latest Articles

If 9 out of 10 interventions are a load of rubbish, what the hell do I DO?August 4, 2022 - 3:29 pm

If 9 out of 10 interventions are a load of rubbish, what the hell do I DO?August 4, 2022 - 3:29 pm Why the advice to “rest” & “remain active” can both be a bit rubbish!December 21, 2021 - 2:38 pm

Why the advice to “rest” & “remain active” can both be a bit rubbish!December 21, 2021 - 2:38 pm Why I HATE discussions about treatment…….June 22, 2021 - 6:58 am

Why I HATE discussions about treatment…….June 22, 2021 - 6:58 am Evidence based practice – Do you love or loathe it?March 29, 2021 - 3:09 pm

Evidence based practice – Do you love or loathe it?March 29, 2021 - 3:09 pm- The myth of exercise prescriptions – It’s probably more trial and error than we care to admitOctober 15, 2020 - 11:43 am

Education in rehab – WTF does it mean…..?October 1, 2020 - 12:15 pm

Education in rehab – WTF does it mean…..?October 1, 2020 - 12:15 pm

SIGN UP FOR UPDATES